Cryovolcanoes on icy moons are some of the wildest, most mind-blowing features in our cosmic backyard. Forget red-hot lava rivers—these are volcanoes that spew ice, liquid water, ammonia slush, and sometimes even organic-rich brines into space. They’re cold, they’re gorgeous, and they’re rewriting everything we thought we knew about where life might hide in the solar system. From Saturn’s tiger-striped Enceladus to Jupiter’s chaotic Europa and distant Pluto, cryovolcanoes are popping up everywhere we look with good cameras. And right now, they’re stealing the spotlight because the same explosive ice-volcano behavior is showing up on an interstellar visitor—yes, we’re talking about NASA’s latest images of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS showing increased activity and potential cryovolcanoes ahead of December 2025 Earth flyby. Buckle up; we’re diving deep into the frozen eruption club.

What Exactly Are Cryovolcanoes on Icy Moons?

Picture Yellowstone’s Old Faithful, but instead of scalding water and steam, you get a geyser of near-freezing saltwater shooting 100 kilometers high in almost zero gravity. That’s a cryovolcano (sometimes called an ice volcano) in a nutshell.

The “cryo” part comes from the Greek word for “frost” or “cold.” These beasts erupt volatiles that are liquid or gaseous only because the surface is so insanely cold—think temperatures between -100 °C and -200 °C. Common eruptive materials include:

- Water (pure or salty)

- Ammonia-water mixtures (acts like antifreeze)

- Methane and nitrogen ices

- Organic slush loaded with carbon compounds

Unlike Earth’s magma-driven volcanoes powered by radioactive decay and mantle convection, cryovolcanoes on icy moons get their energy from tidal heating, internal radioactivity, or pressure changes in subsurface oceans. The result? Plumes that can reach space and feed giant planetary ring systems.

Enceladus: The Undisputed Cryovolcano Superstar

If cryovolcanoes on icy moons had a poster child, it’s Enceladus, Saturn’s 500-km-wide snowball. Those iconic tiger stripes at its south pole—four parallel fractures nicknamed “Alexandria,” “Cairo,” “Baghdad,” and “Damascus”—are actually hot cracks where cryovolcanoes blast continuously.

Cassini flew through those plumes multiple times between 2005 and 2017 and tasted:

- 98% water vapor

- Salt grains (proof of a global subsurface ocean)

- Complex organic molecules up to 200 atomic mass units

- Tiny silica particles that only form in warm (at least 90 °C) hydrothermal conditions

That’s right: a moon smaller than the United Kingdom has a salty, warm ocean capped by an ice shell only 5–30 km thick, and it’s venting like crazy. Scientists now estimate over 100 cryovolcanoes are active along those tiger stripes at any given time, pumping out roughly 200–300 kg of material per second. No wonder Saturn’s faint E-ring is almost entirely made of Enceladus snow!

Europa: Cryovolcanoes or Water-Vapor Plumes?

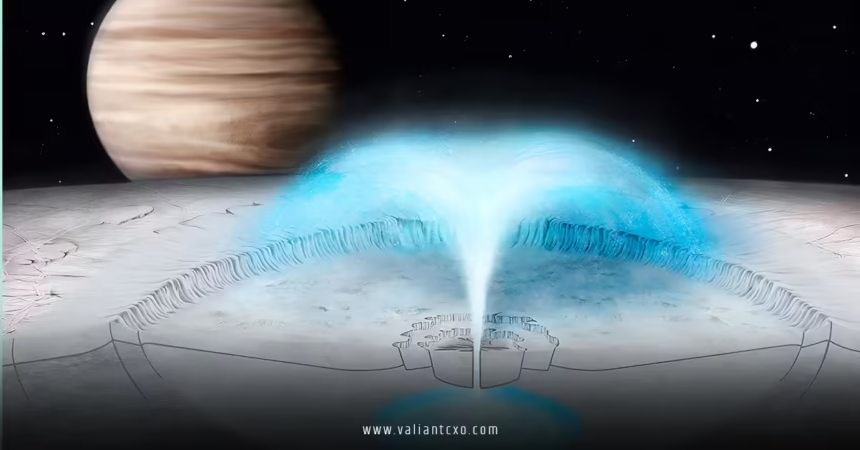

Jupiter’s Europa is the bad-boy sibling—covered in lineae (those reddish cracks) and possible chaos terrain where the ice shell has collapsed into slush. Hubble spotted water-vapor plumes in 2013, 2016, and again in 2022, rising up to 200 km above the surface.

Are they true cryovolcanoes on icy moons? Debate still rages. Some researchers think they’re narrow jets from tidal cracking (more geyser than volcano), while others point to dome-shaped features and flow-like deposits as evidence of thicker, slushy eruptions. Either way, Europa’s plumes are probably tapping the same global ocean that hides beneath 10–30 km of ice. NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission (launch 2024, arrival 2030) will fly through any plumes it finds and sniff for signs of life.

Titan: The King of Confirmed Cryovolcanoes

Saturn’s biggest moon, Titan, wins the prize for the most unambiguous cryovolcanoes on icy moons. Cassini radar and infrared instruments spotted:

- Doom Mons – a 1.5-km-high mountain with a deep central crater

- Sotra Patera – a 30-km-wide depression with 1-km-high rims and lava-like flow features

- Hundreds of smaller candidates

Instead of water, Titan’s cryovolcanoes probably erupt liquid methane and ammonia mixtures. Imagine rivers of natural gas bursting out and freezing into icy lava flows across a landscape that already looks eerily like Earth—complete with lakes, dunes, and rain.

Pluto and Triton: Cryovolcanism at the Edge of the Solar System

Even out in the Kuiper Belt, cryovolcanoes refuse to be ignored. New Horizons flew past Pluto in 2015 and photographed Wright Mons and Piccard Mons—massive features with central depressions and hummocky textures that scream “ice volcano.” Some researchers think they’re only a few million years old, meaning Pluto is still geologically alive.

Neptune’s moon Triton, captured from the Kuiper Belt billions of years ago, put on a show for Voyager 2 in 1989: dark plumes rising 8 km high and drifting 150 km downwind. Nitrogen geysers, yes—but driven by a greenhouse effect under transparent ice, a unique twist on the cryovolcano theme.

How Do Cryovolcanoes on Icy Moons Actually Work?

Let’s break down the recipe:

- Subsurface liquid reservoir – usually a global or regional ocean kept warm by tidal flexing (Io-style, but for ice instead of rock).

- Pressure buildup – from freezing (expands), gas exsolution, or tidal cracking.

- Conduit to the surface – a fracture or weak spot in the ice shell.

- Violent release – the low gravity and vacuum of space let plumes reach insane heights.

Add a dash of salts or ammonia to lower the freezing point, and boom—cryovolcanic eruption.

Why Cryovolcanoes on Icy Moons Are an Astrobiologist’s Dream

Here’s the part that gives scientists goosebumps: cryovolcanoes are nature’s free sample return missions. Every plume carries material straight from a hidden ocean to space, where a spacecraft can fly through and taste it without drilling. Enceladus already proved the ocean is salty, warm, has energy sources (hydrothermal vents), and contains complex organics. That ticks every box for potential habitability.

If you’re hunting alien life, cryovolcanoes on icy moons just handed you the cheat code.

The Surprising Link to Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS

Here’s where things get even crazier. In late 2025, astronomers using Hubble and other telescopes spotted what look like cryovolcanic outbursts on an object that doesn’t even belong to our solar system—interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS. That’s right: the same kind of icy eruptions we see on Enceladus and Europa might be happening on a comet that formed around another star billions of years ago.

NASA’s latest images of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS showing increased activity and potential cryovolcanoes ahead of December 2025 Earth flyby reveal bright jets and a rapidly growing coma that don’t match normal sun-driven sublimation. Researchers now think pockets of ammonia or carbon-monoxide ice are explosively venting—mini cryovolcanoes on a rogue worldlet. It’s the first time we’ve seen cryovolcanic-style activity beyond our own planetary family, hinting that these frozen fireworks might be common throughout the galaxy.

The Future: Missions That Will Blow Our Minds

- Europa Clipper (2030) – 50+ plume fly-throughs planned

- Dragonfly to Titan (launch 2028, arrival 2034) – will land near possible cryovolcano Selk crater

- Proposed Enceladus orbiters and plume sample-return concepts

- JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) – Ganymede-focused but will study Europa and Callisto too

Every one of these missions has cryovolcanoes on icy moons squarely in their crosshairs.

Final Thoughts: Ice That Burns with Possibility

Cryovolcanoes on icy moons aren’t just geological curiosities—they’re windows into hidden oceans, messengers of potential life, and now, thanks to comet 3I/ATLAS, proof that this phenomenon might be a universal feature of icy bodies everywhere. From Enceladus raining into Saturn’s rings to Pluto coughing up fresh ice on the galaxy’s edge, our solar system is alive with cold fire.

Next time someone says space is boring, show them a picture of Enceladus’ tiger stripes glowing against the void. Tell them that under that ice lies an ocean that might be more habitable than Earth’s. And remind them that even objects from other star systems are joining the cryovolcanic party.

The universe isn’t dead rock and gas—it’s erupting with frozen possibility.